Ka`awaloa, South Kona, Hawaii

From the Collections of Kona Historical Society.

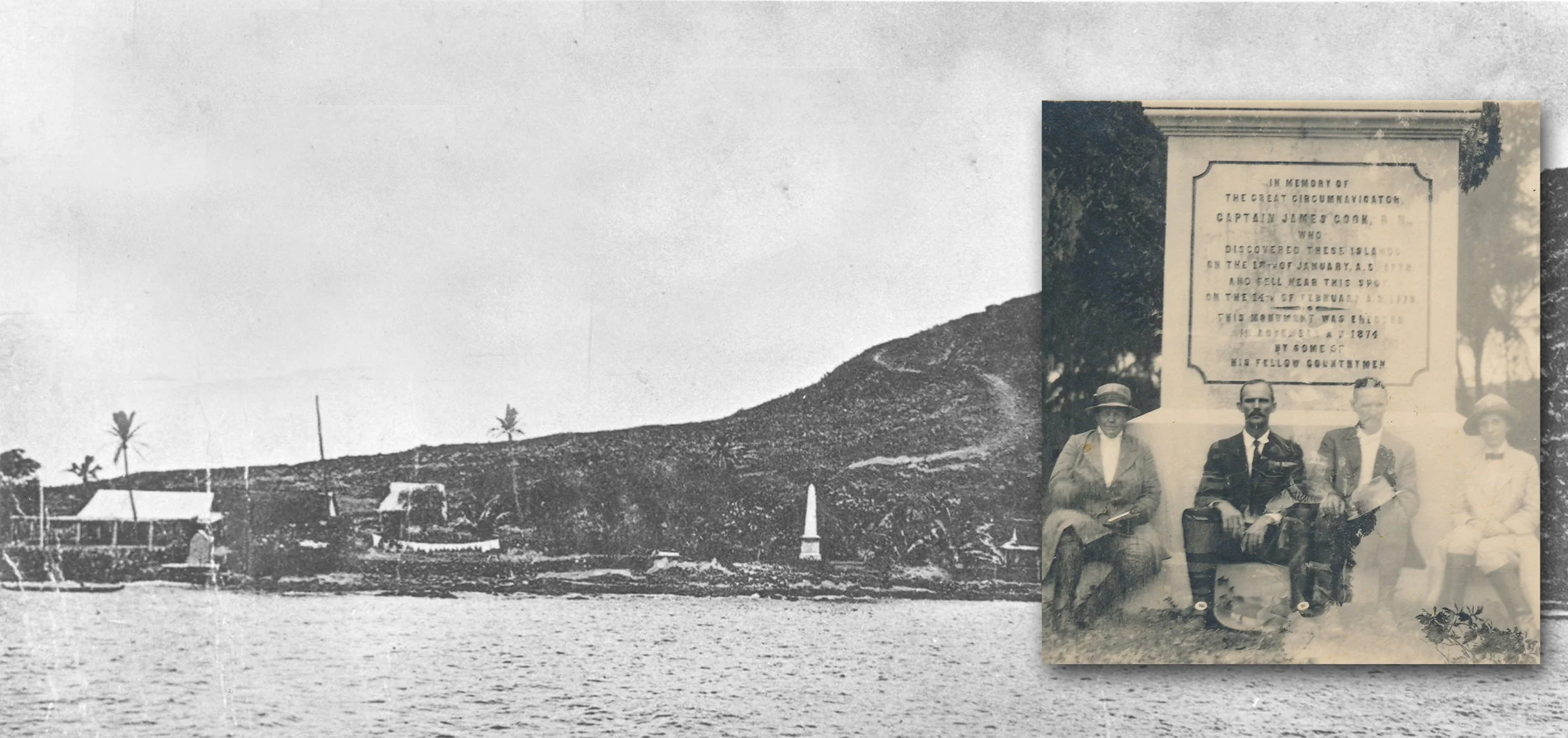

Here is view of Ka`awaloa, at one time a Hawaiian village and royal residence on Kealakekua Bay’s northern edge. It was a happening place and home of Hawaii’s most royal hosts and hostesses during the last quarter of the 18th century. Today Ka`awaloa is famous by its association with Captain James Cook for it was on these rocks England’s great navigator and explorer was killed on February 14, 1779.

This photograph was probably taken in the late 19th century, although possibly it dates from the early 20th century. The tall white spire to the right is the concrete monument erected to Cook’s memory in 1874 by men aboard HMS Scout, a British naval vessel which came to the islands carrying that country’s Transit of Venus scientific expedition. To learn more about this astronomical endeavor, Michael Chauvin’s wonderful book Hokuloa (Bishop Museum Press, 2004) is a must read. In it you will discover how British Commissioner Wodehouse traveled on board HMS Scout from Honolulu to Kona to see Cook’s memorial obelisk erected. Up until that time, much to Britain’s disgrace, Cook’s only monument at the place of his death was a coconut stump. Over the years, visiting sea captains had covered the stump with copper sheets taken from the hulls of their ships, inscribing dates and names in the soft metal. When American Mark Twain visited Kaawaloa in 1866, he mocked the mighty empire that remembered Cook with such a miserable edifice. Who knows if Twain’s sarcastic words stung the British Empire or whether the upcoming 100th anniversary of his death spurred it into action?

In 1779, Ka`awaloa was a thriving village of grass thatched houses, tidy stone walls, an important temple complex, healthy coconut palms, and numerous inhabitants. Webber, the artist assigned to Cook’s third voyage, recorded its appearance in a few of his drawings, the earliest record we have of this place. Look in the background of the famous engraving of masked canoe paddlers in Kealakekua Bay. You will see Ka`awaloa in the background, thickly shaded by foliage and palms.

When Captain George Vancouver, who had been with Cook in 1779, returned to Kealakekua Bay in 1792, not much had changed. Ka`awaloa was still a residence of choice for Kona chiefs, especially during the winter Makahiki season. With King Kalaniopu`u dead, Kamehameha was then ruling chief of Kona, and soon after, of all the Hawaiian Islands. If it were possible to be a fly on the wall of Kealakekua’s cliffs in 1793, we would have seen Vancouver unloading California cattle into canoes in these waters. We would have witnessed Queen Ka`ahumanu and Kamehameha patching up their lover’s quarrel on board Vancouver’s ship. We would have shuddered in fear and delight as explosions of fireworks lighted up the inky night skies over the bay, a popular 18th century entertainment produced by the English for their Hawaiian hosts.

One hundred years later, as this photo clearly shows, the village was scarcely populated at all. Although Ka`awaloa had become a regular port of call for inter-island steamers, its native population had plummeted. The Hawaiian chiefly families who once called this place home had died or moved to Honolulu. Brave Chiefess Kapi`olani (1781-1841), who dared to face the Volcano goddess Pele at Kilauea’s craters, hailed from Ka`awaloa, as did the family of King Kalakaua. Princess Miriam Likelike had a home at Ka`awaloa until her death in 1887, a home she kindly offered to writer Isabella Bird as a rest stop in 1873. In Henry Nicholas Greenwell’s journal, he made this entry: October 16, 1885. “HNG at Kalukalu. A grand Luau was given today at Kaawaloa by Mrs. Cleghorn in honor of the birthday of her daughter the Princess Kaiulani. Carrie, Lily, Christina and their Aunt went down.” How we wish there was a photograph to record that happy and innocent 10th birthday celebration, a bright day in a young girl’s life that would end amid sorrow and tears not fourteen years later.

One of the structures visible may be Barrett’s Hotel. Englishman Daniel Barrett and his Hawaiian wife had a rather rough and tumble establishment for invalids in search of warm air and stranded passengers waiting for the Kilauea to arrive. Clearly visible on the hillside above is one of Kona’s first commercial roads snaking up the cliff behind the monument. Governor Kuakini ordered this cart road built up to the main Government Road at 1,400 feet, not far from missionary John D. Paris’ home at Mauna Alani. Much of the labor was provided by people who had engaged in “rascal sleeping” or moe kolohe, a punishable offense in the early 19th century era of Missionary law. In the foreground, to the left of the monument, is a line of white laundry hanging out to dry, a cheerful domestic note no longer seen at Ka`awaloa.

Our second photograph is of note because author Charmian London, Jack London’s widowed wife, is seated at the far right in her attractive riding outfit. The year may be 1920 because in Charmian’s book, Our Hawaii, she wrote on page 415: “One novel trip to me was on horseback to Kaawaloa, where is the Cook monument. The trail lies down a rocky ridge, on which one sees the site of that small heiau where Captain Cook’s body was dismembered, and where one may turn aside to look upon Lord Byron’s 1825 oaken cross with tablet to the memory of his slain countryman.

“……The scene that is stamped upon my recollection is of the peacock-blue, deep water at foot of that dull-gold burial cliff.”

Who she did not mention were her riding companions, seated from left to right: Miss Bertha Ben Taylor, Supervising Principal of the West Hawaii government schools from 1911 to 1920; rancher Arthur Leonard Greenwell of Kealakekua; and his older brother, William Henry Greenwell of Kalukalu. This photo came into the Kona Historical Society Collection after the death of Maud Greenwell, widow of W.H. Greenwell. Mrs. London looks cool and crisp in white, while the Greenwell men, handsome but hot, persist in wearing dark jackets and ties at sea level. Miss Ben Taylor, formidable and well respected, appears ready for a jaunt on the Yorkshire moors!

At the beginning of Charmian’s Our Hawaii, she bemoans the fact she had to put a skirt on over her trousers to ride a horse on Oahu. “..could not stifle a sigh as I blotted out the natty boyish togs with the long, hot black skirt.” That was in 1907. Apparently, by 1920, she felt able ride in Kona without her dark, sweltering skirt – hooray! Charmian always admired what she called “the cross-saddle horse craft of women in Honolulu.”

In 2012, the State of Hawaii is still grappling with how to interpret the history of Ka`awaloa. Meanwhile, thousands of visitors have paddled in and over the bay’s peacock blue waters, wandered over the lava to see where Cook fell, and paused to enjoy a truly magnificent landscape. Ka`awaloa today is more desolate and unpopulated than it appeared one hundred years ago. Cook and Vancouver, Kalaniopu`u and Kamehameha would all be surprised.

Aloha no, e Kona.